Many expats mistakenly assume that having a visa or living part-time in Italy automatically makes them residents, or, conversely, that they can freely spend time in Italy without triggering tax consequences. In reality, Italy uses a combination of physical presence, registry status, and personal ties to determine residency, and once residency is established, obligations extend beyond local earnings.

Recent updates to Italy’s tax rules have reshaped how individuals—especially expats—are classified for tax purposes. In 2024 the Italian Revenue Service (Agenzia delle Entrate) clarified the meaning of tax residency, making it easier for newcomers to determine whether and when they are considered part of the Italian tax system. Understanding these criteria is essential for anyone planning to live, work, or spend significant time in Italy, as tax residency affects how income is taxed and what financial reporting is required.

Determining Your Tax Residency Status

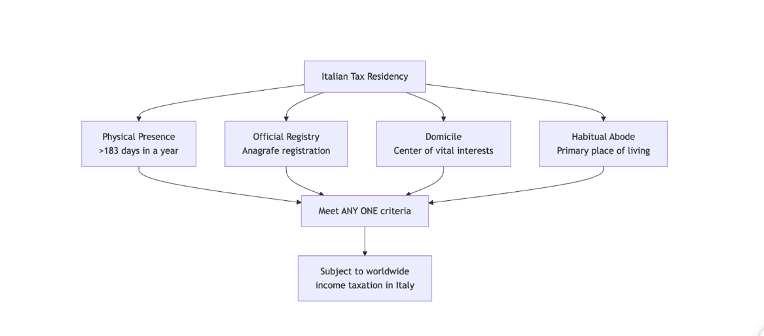

Italian law establishes tax residency based on several independent criteria. Meeting any one of them for more than half the calendar year (over 183 days, or 184 in leap years) is enough for Italy to regard an individual as a tax resident. The criteria include:

- Physical Presence: Spending more than 183 days in Italy—whether consecutively or spread throughout the year—can result in tax residency. Italy counts both full days and partial days toward the total, including arrival and departure days.

- Registration in the Local Resident Registry (Anagrafe della Popolazione Residente): registering to the municipal registry of residents can creates a strong presumption of residency for tax purposes. Although this presumption can be challenged in limited cases, it is generally treated as a significant indicator of residence.

- Domicile: A person is considered domiciled in Italy when their primary personal and family connections are centered there. This focuses on where an individual’s life is socially, emotionally, and relationally based rather than merely where they own property or hold citizenship.

- Habitual Residence: it refers to Italy being the place an individual consistently lives and carries out daily life. Even if someone remains registered elsewhere, day-to-day living in Italy may be enough to be treated as resident for tax purposes.

Under the revised rules, any single factor can independently trigger tax residency once the “more than half the year” threshold is satisfied.

Key Considerations for the 183-Day Rule

The 183-day calculation is affected by two main practical details, the first one being how days are counted. As previously mentioned, every day spent in Italy contributes to the total, including fractions of days. Moreover, these days do not need to be consecutive. This means that, even if you do not spend 183 consecutive days in Italy, but the sum of all the days equals or exceeds 183 days, you will be subject to taxation.

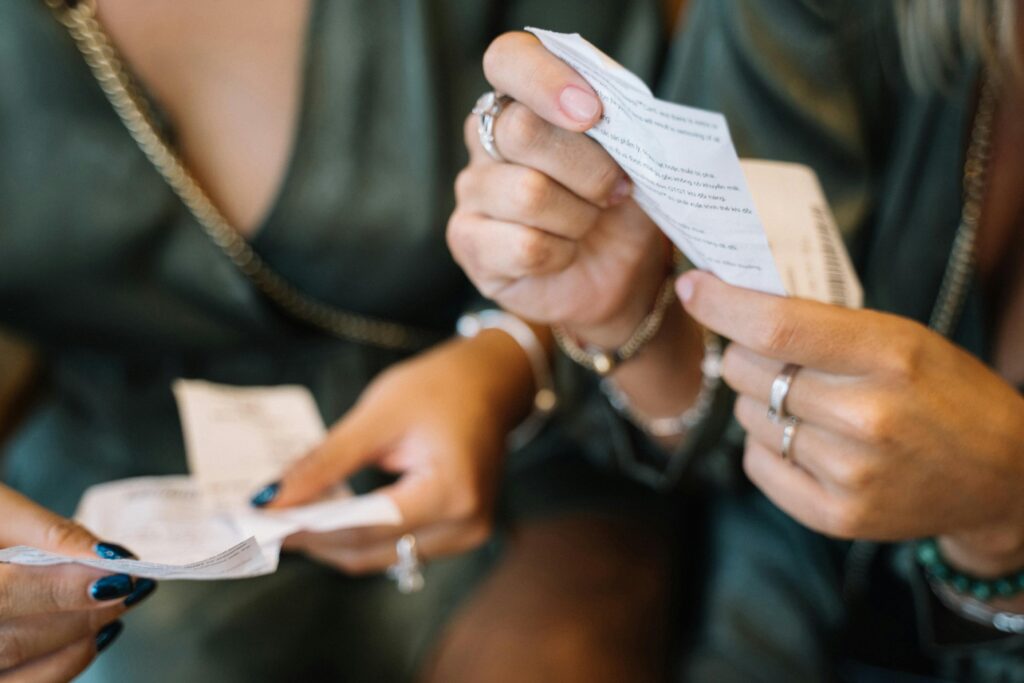

Another important weighting factor is documentation, as proof may be required if residency status is later examined. Travel records, airline tickets, passport stamps, accommodation contracts, and similar documentation can serve as evidence should the tax authorities request it, so it is crucial to keep them.

What Happens Once You Become a Tax Resident

Being classified as a tax resident means individuals are subject to Italian tax rules on a broad basis, which includes:

- Worldwide Taxation: Residents must declare and pay Italian taxes on your income worldwide, not solely on income earned within Italy.

- Mandatory Annual Tax Return: Tax residents are required to file an annual Italian Tax return. Employees and pensioners usually file through the simplified Modello 730, while freelancers, investors, and self-employed individuals typically file through Modello Redditi. The deadlines typically fall in June or November.

- Foreign Asset Reporting: Foreign bank accounts, securities, investments, and real estate must be disclosed annually through specific sections of the tax return (such as Quadro RW), and may result in additional tax obligations.

In cases where someone qualifies as a tax resident in two countries simultaneously, bilateral tax treaties help determine which country has primary taxing rights and how to avoid being taxed twice. Documentation such as residency certificates is often required to claim treaty relief.

For expats who do become residents, it’s important to explore whether they may qualify for any of the available Italian tax incentives that can significantly reduce the overall tax burden.

Important Factors for Expats to Consider

When deciding whether applying for residency is the right choice for you, several additional factors should be considered.

The first factor would be the family location, as spouse or dependent children living with you in Italy can weigh heavily in favor of residency.

Another imortant aspect to consider would be the economic interests in establishing residency: conducting business, earning income, or holding assets in Italy may factor into domicile assessments.

Then, if you entered with or plan to apply for Visa to be able to stay longer than 90 days, a residence permit (Permesso di Soggiono) must be requested upon your arrival. This is often connected to registry requirements.

Lastly, the legal definitions of “domicile” and “habitual residence” are evolving as reforms continue to roll out, so it is crucial to be up-to-date with these changes.

Leaving Italy

Residents who decide to depart Italy must formally deregister from the Anagrafe and establish residency elsewhere. Without proper deregistration, Italy may continue to treat the person as a tax resident, which can create ongoing tax obligations—an important point for remote workers, digital nomads, and globally mobile professionals.

Core Takeaway

If you spend more than 183 days in Italy, register as a resident, or establish your personal and economic ties there, Italy is likely to treat you as a tax resident. This unlocks a comprehensive set of tax obligations, particularly relating to foreign income and asset reporting. Staying compliant requires good record-keeping, awareness of international tax treaties, and clear planning before entering or leaving the Italian system.